As the world prepares to welcome Beyonce’s 8th studio album, “Cowboy Carter,” your friends here at The Rhapsody Project are working to ensure that you have brass tacks and firm facts at your fingertips to supply when the yahoos start kvetching that this album is not, in fact, properly classified as “country.”

Ever since Americans have created original art, other Americans have repurposed that art to tell a different story. Who profits & who is visible in the wake of each adaptation says most of what you need to know about whether that love and theft is creative and just, or appropriative and harmful.

With “Cowboy Carter” we have a textbook case of the Good ‘Ol Boys in Nashville white-knuckling their grip on the levers of power that control the gates of The Country Music machine. As Jon Caramanica recently observed in the New York Times:

“… whether or not Beyoncé and Nashville can find common cause is, in every way, a red herring. Neither is particularly interested in the other — the tradition-shaped country music business will accept certain kinds of outsiders but isn’t set up to accommodate a Black female star of Beyoncé’s stature, and she is focusing on country as art and inspiration and sociopolitical plaything, not industry. The spurn is mutual.”

Will Country Welcome Beyoncé? That’s the Wrong Question.

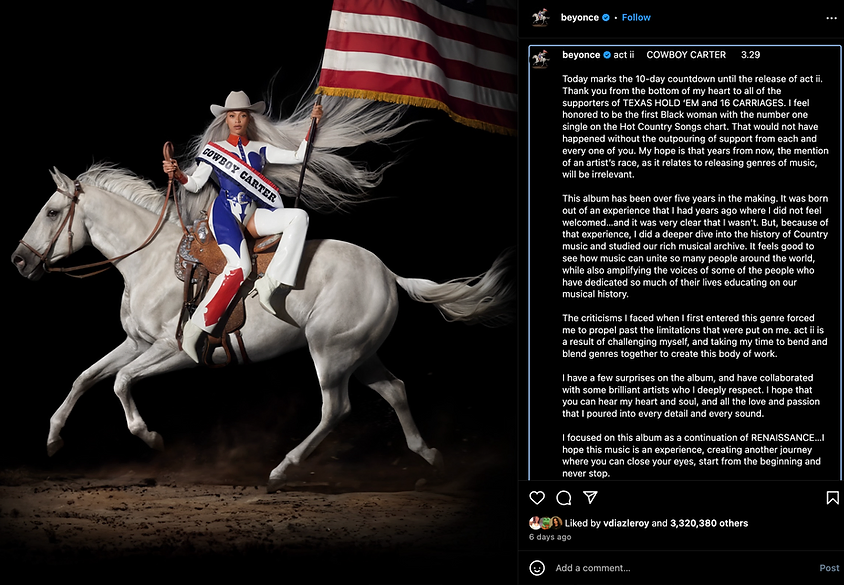

The ways in which Beyoncé is playing with country music shows that she understands it as a living tradition. Living traditions are vital enough to change and be changed to reflect the people that they sustain. But, the gatekeepers of the country music industry harmed Beyoncé in a lasting way, and so she’s ignoring them while making music that cannot be ignored:

The criticism Beyonce was confronted with is, of course, partly plain-old racism. It’s also the good, old-fashioned product of the powerful grasping when their power gets threatened. But what she’s doing is also complicated, and has been done on other levels by many other Black artists in prior eras.

You can learn the complexity woven into these seemingly simple patterns when we study the traditions of American dance – for instance, check out the history of the cakewalk – as well as music.

One stellar musical example of creative adaptation comes from the exceedingly joyful and upbeat spin that The Golden Gate Quartet put on a Stephen Foster song from 1852. “Massa’s in the Cold Ground” was conceived as a dirge, telling the story of enslaved people mourning the death of their owner. When you pay attention to the spirit of The Golden Gate Quartet’s lovely performance, there is no question of what their feelings are about “Massa’s” departure:

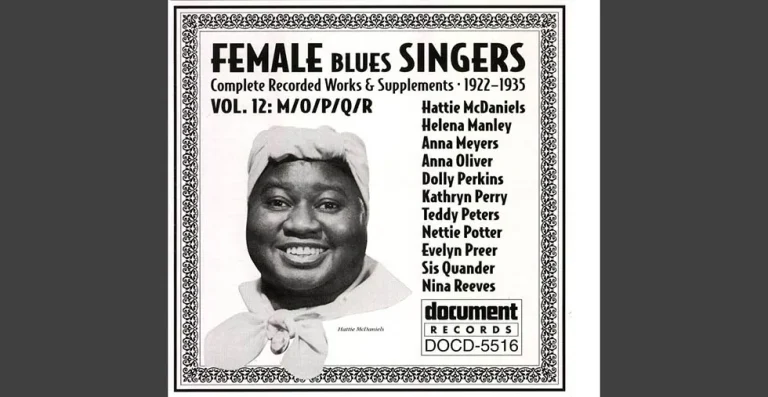

While this particular example gives us an ensemble of Black musicians adapting a white composer’s work, there are – of course – thousands of examples of white musicians or composers profiting off of the creations of Black artists. This happened with the song “Dixie” long before the more ballyhooed example of Elvis appropriating Willie May “Big Mama” Thorton’s “You Ain’t Nothin’ But a Hound Dog.”

Black Americans were not merely responsible for the genesis of the genres they are (generally) credited with creating – the spirituals, ragtime, blues, jazz, rock ‘n roll, funk, and hip hop, to name a few – they were a foundational part of “country” music long before it was a genre.

Look no further than the origins of the banjo to discover one way in which this is the case. But, one thing you may not know about the wordplay in Beyonce’s chosen album title is this:

“The Carter Family” is the name given to a group often termed, “The First Family of Country Music” – and tons of their source material came from . . . wait for it . . . Black people.

As lovingly documented in the fabulous book, Will You Miss Me When I’m Gone: The Carter Family & Their Legacy in American Music, A.P. Carter would walk the Appalachian hills with his friend, Lesley Riddle – a Black man and guitar player with a keen ear for melodies – and seek out new songs for his family band to record and perform. A.P. would write down the lyrics, Riddle would memorize the melodies, and they would go back to the Carter home for Riddle to teach the melodies to the family.

After contemplating such stories and artistic journeys as those of the Golden Gate Quartet and the Carter Family, it is impossible to see how – no matter her sophistication, urbanity, popularity, or ubiquity – one could wisely disqualify Beyonce Knowles (a woman raised Texas, of all places) from the realm of “country” music.

Thus, we welcome the growth of the genre and invite all of those who are trying to delve into Black American History through music.

Want to help The Rhapsody Project share more stories and resources like these? Become a Resonator today!